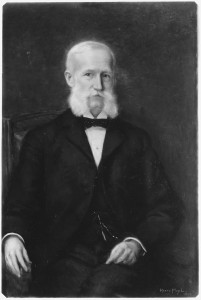

John Watson Foster was a Civil War veteran, American diplomat, lawyer, and journalist. He reached the pinnacle of his public career as U.S. Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison but also wielded influence as an international lawyer in private practice.

Born on March 2, 1836, in Petersburg, Indiana, Foster grew up in Evansville as the son of Indiana farmer Matthew Watson and Eleanor Foster (née Johnson). He graduated as class valedictorian from Indiana University in 1855. Though his parents hoped he would become a preacher, Foster chose law. He graduated from Harvard Law School and started his legal career in Cincinnati, Ohio. During the 1960 election, he was an abolitionist and campaigned for President Lincoln.

In 1861, Foster joined the Union Army. Starting as a major, he rose to colonel, serving in various Indiana Volunteer Infantry regiments. His troops were the first to enter Knoxville, Tennessee, following a successful campaign by General Ambrose Burnside.

Despite viewing war as a futile endeavor, a belief dating back to his college days, Foster found his health and spirits lifted by the rigors of military life. Yet, unlike many contemporaries who romanticized war, Foster’s fascination with its so-called glories waned over time. When he later published his wartime memories, he emphasized that his experiences had only deepened his opposition to war.

After the Civil War, Foster returned to Indiana and edited the Evansville Daily Journal. By 1869, he became Evansville’s postmaster and chaired Indiana’s Republican State Central Committee. For his efforts, Republican Presidents Grant, Hayes, and Garfield appointed him U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, then Russia. President Arthur later made him Ambassador to Spain.

Back in the U.S., Foster settled in Washington, D.C. He served as a State Department troubleshooter before becoming Secretary of State in the final months of Harrison’s term. In this role, he played a part in overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy.

After public service, Foster remained in Washington, pioneering a new form of legal practice that involved lobbying for corporations. He also secured legal fees as counsel to foreign legations and continued part-time diplomatic work, negotiating various international agreements.

Foster authored several books, including “American Diplomacy in the Orient” in 1903 and “Arbitration and the Hague Court” in 1904. He died on November 15, 1917, and was buried in Evansville’s Oak Hill Cemetery.

His legacy lived on through his family. His daughter Edith married Presbyterian minister Allen Macy Dulles, parents to John Foster Dulles, a future U.S. Secretary of State, and Allen Welsh Dulles, later Director of Central Intelligence. Another daughter, Eleanor, married State Department legal advisor Robert Lansing; their daughter Eleanor Lansing Dulles became an economist and diplomat. Foster is also the great-grandfather of theologian Cardinal Avery Dulles.